Arizona

History

Evidence of a human presence in Arizona dates back more than 12,000 years. The first Arizonans—the offshoot of migrations across the Bering Strait—were large-game hunters: their remains have been found in the San Pedro Valley in the southeastern part of the state. By AD 500, their descendants had acquired a rudimentary agriculture from what is now Mexico and divided into several cultures. The Basket Makers (Anasazi) flourished in the northeastern part of the state; the Mogollon hunted and foraged in the eastern mountains; the Hokoham, highly sophisticated irrigators, built canals and villages in the central and southern valleys: and the Hakataya, a less-advanced river people, lived south and west of the Grand Canyon. For reasons unknown—a devastating drought is the most likely explanation—these cultures were in decay and the population much reduced by the 14th century. Two centuries later, when the first Europeans arrived, most of the natives were living in simple shelters in fertile river valleys, dependent on hunting, gathering, and small-scale farming for subsistence. These Arizona Indians belonged to three linguistic families: Uto-Aztecan (Hopi, Paiute, Chemehuevi, Pima-Papago), Yuman (Yuma, Mohave, Cocopa, Maricopa, Yavapai, Walapai, Havasupai), and Athapaskan (Navaho-Apache). The Hopi were the oldest group, their roots reaching back to the Anasazi; the youngest were the Navaho-Apache, migrants from the Plains, who were not considered separate tribes until the early 18th century.

The Spanish presence in Arizona involved exploration, missionary work, and settlement. Between 1539 and 1605, four expeditions crossed the land, penetrating both the upland plateau and the lower desert in ill-fated attempts to find great riches. In their footsteps came Franciscans from the Rio Grande to work among the Hopi; and Jesuits from the south, led by Eusebio Kino in 1692, to proselytize among the Pima. Within a few years, Kino had established a major mission station at San Xavier del Bac, near present-day Tucson. In 1736, a rich silver discovery near the Pima village of Arizona, about 20 mi (32 km) southwest of present-day Nogales, drew Spanish prospectors and settlers northward. To control the restless Pima, Spain in 1752 placed a military outpost, or presidio, at Tubac on the Santa Cruz River north of Nogales. This was the first major European settlement in Arizona. The garrison was moved north to the new fort at Tucson, also on the Santa Cruz, in 1776. During these years, the Spaniards gave little attention to the Santa Cruz settlements, administered as part of the Mexican province of Sonora, regarding them merely as way stations for colonizing expeditions traveling overland to the highly desirable lands of California. The end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th were periods of relative peace on the frontier; mines were developed and ranches begun. Spaniards removed hostile Apache bands onto reservations and made an effort to open a road to Santa Fe.

When Mexico revolted against Spain in 1810, the Arizona settlements were little affected. Mexican authorities did not take control at Arizpe, the Sonoran capital, until 1823. Troubled times followed, characterized by economic stagnation, political chaos, and renewed war with the Apache. Sonora was divided into partidos (counties), and the towns on the Santa Cruz were designated as a separate partido, with the county seat at Tubac. The area north of the Gila River, inhabited only by Indians, was vaguely claimed by New Mexico. With the outbreak of the Mexican War in 1846, two US armies marched across the region: Col. Stephen W. Kearny followed the Gila across Arizona from New Mexico to California, and Lt. Col. Philip Cooke led a Mormon battalion westward through Tucson to California. The California gold rush of 1849 saw thousands of Americans pass along the Gila toward the new El Dorado. In 1850, most of present-day Arizona became part of the new US Territory of New Mexico; the southern strip was added by the Gadsden Purchase in 1853.

Three years later, the Sonora Exploring and Mining Co. organized a large party, led by Charles D. Poston, to open silver mines around Tubac. A boom followed, with Tubac becoming the largest settlement in the valley; the first newspaper, the Weekly Arizonian, was launched there in 1859. The great desire of California for transportation links with the rest of the Union prompted the federal government to chart roads and railroad routes across Arizona, erect forts there to protect Anglo travelers from the Indians, and open overland mail service. Dissatisfied with their representation at Santa Fe, the territorial capital, Arizona settlers joined those in southern New Mexico in 1860 in an abortive effort to create a new territorial entity. The outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 saw the declaration of Arizona as Confederate territory and abandonment of the region by the Union troops. A small Confederate force entered Arizona in 1862 but was driven out by a volunteer Union army from California. On 24 February 1863, President Abraham Lincoln signed into law a measure creating the new Territory of Arizona. Prescott became the capital in 1864, Tucson in 1867, Prescott again in 1877, and finally Phoenix in 1889.

During the early years of territorial status, the development of rich gold mines along the lower Colorado River and in the interior mountains attracted both people and capital to Arizona, as did the discovery of silver bonanzas in Tombstone and other districts in the late 1870s. Additional military posts were constructed to protect mines, towns, and travelers. This activity, in turn, provided the basis for a fledgling cattle industry and irrigated farming. Phoenix, established in 1868, grew steadily as an agricultural center. The Southern Pacific Railroad, laying track eastward from California, reached Tucson in 1880, and the Atlantic and Pacific (later acquired by the Santa Fe), stretching west from Albuquerque through Flagstaff, opened service to California in 1883. By 1890, copper had replaced silver as the principal mineral extracted in Arizona. In the Phoenix area, large canal companies began wrestling with the problem of supplying water for commercial agriculture. This problem was resolved in 1917 with the opening of the Salt River Valley Project, a federal reclamation program that provided enormous agricultural potential.

As a creature of the Congress, Arizona Territory was presided over by a succession of governors, principally Republicans, appointed in Washington. In reaction, the populace was predominantly Democratic. Within the territory, a merchant-capitalist class, with strong ties to California, dominated local and territorial politics until it was replaced with a mining-railroad group whose influence continued well into the 20th century. A move for separate statehood began in the 1880s but did not receive serious attention in Congress for another two decades. In 1910, after Congress passed an enabling act that allowed Arizona to apply for statehood, a convention met at Phoenix and drafted a state constitution. On 14 February 1912, Arizona entered the Union as the 48th state.

During the first half of the 20th century, Arizona shook off its frontier past. World War I (1914–18) spurred the expansion of the copper industry, intensive agriculture, and livestock production. Goodyear Tire and Rubber established large farms in the Salt River Valley to raise pima cotton. The war boom also generated high prices, land speculation, and labor unrest; at Bisbee and Jerome, local authorities forcibly deported more than 1,000 striking miners during the summer of 1917. The 1920s brought depression: banks closed, mines shut down, and agricultural production declined. To revive the economy, local boosters pushed highway construction, tourism, and the resort business. Arizona also shared in the general distress caused by the Great Depression of the 1930s and received large amounts of federal aid for relief and recovery. A copper tariff encouraged the mining industry, additional irrigation projects were started, and public works were begun on Indian reservations, in parks and forests, and at education institutions. Prosperity returned during World War II (1939–45) as camps for military training, prisoners of war, and displaced Japanese-Americans were built throughout the state. Meat, cotton, and copper markets flourished, and the construction of processing and assembly plants suggested a new direction for the state's economy.

Arizona emerged from World War II as a modern state. War industries spawned an expanding peacetime manufacturing boom that soon provided the principal source of income, followed by tourism, agriculture, and mining. During the 1950s, the political scene changed. Arizona Republicans captured the governorship, gained votes in the legislature, won congressional seats, and brought a viable two-party system to the state. The rise of Barry Goldwater of Phoenix to national prominence further encouraged Republican influence. Meanwhile, air conditioning changed lifestyles, prompting a significant migration to the state.

But prosperity did not reach into all sectors. While the state ranked as only the 19th poorest in the nation in 1990 (with a poverty rate of 13.7%), by 1998, it ranked 6th poorest, with a poverty rate of 16.6%.

For many years Arizona had seen its water diverted to California. In 1985, however, the state acted to bring water from the Colorado River to its own citizens by building the Central Arizona Project (CAP). The CAP was a $3 billion network of canals, tunnels, dams and pumping stations which had the capacity to bring 2.8 million acre-feet of water a year from the Colorado River to Arizona's desert lands, cities, and farms. By 1994, however, many considered the project to be a failure, as little demand existed for the water it supplied. Farmers concluded that water-intensive crops such as cotton were not profitable, and Arizona residents complained that the water provided by the CAP was dirty and undrinkable.

Arizona politics in recent years has been rocked by the discovery of corruption in high places. In 1988, Governor Evan Mecham was impeached on two charges of official misconduct. In 1989, Senators John McCain and Dennis DeConcini were indicted for interceding in 1987 with federal bank regulators on behalf of Lincoln Savings and Loan Association. Lincoln's president, Charles Keating, Jr., had contributed large sums to the Senators' reelection campaigns. In 1990, Peter MacDonald, the leader of the Navajo Nation, was convicted in the Navajo Tribal Court of soliciting $400,000 in bribes and kickbacks from corporations and individuals who sought to conduct business with the tribe in the 1970s and 1980s. A year later, seven members of the Arizona state legislature were charged with bribery, money laundering, and filing false election claims as the result of a sting operation. The legislators were videotaped accepting thousands of dollars from a man posing as a gaming consultant in return for agreeing to legalize casino gambling.

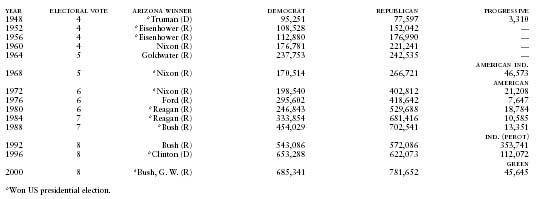

Arizona Presidential Vote by Political Party, 1948–2000

| YEAR | ELECTORAL VOTE | ARIZONA WINNER | DEMOCRAT | REPUBLICAN | progressive |

| *Won US presidential election. | |||||

| 1948 | 4 | *Truman (D) | 95,251 | 77,597 | 3,310 |

| 1952 | 4 | *Eisenhower (R) | 108,528 | 152,042 | — |

| 1956 | 4 | *Eisenhower (R) | 112,880 | 176,990 | — |

| 1960 | 4 | Nixon (R) | 176,781 | 221,241 | — |

| 1964 | 5 | Goldwater (R) | 237,753 | 242,535 | — |

| AMERICAN IND. | |||||

| 1968 | 5 | *Nixon (R) | 170,514 | 266,721 | 46,573 |

| AMERICAN | |||||

| 1972 | 6 | *Nixon (R) | 198,540 | 402,812 | 21,208 |

| 1976 | 6 | Ford (R) | 295,602 | 418,642 | 7,647 |

| 1980 | 6 | *Reagan (R) | 246,843 | 529,688 | 18,784 |

| 1984 | 7 | *Reagan (R) | 333,854 | 681,416 | 10,585 |

| 1988 | 7 | *Bush (R) | 454,029 | 702,541 | 13,351 |

| IND. (PEROT) | |||||

| 1992 | 8 | Bush (R) | 543,086 | 572,086 | 353,741 |

| 1996 | 8 | *Clinton (D) | 653,288 | 622,073 | 112,072 |

| GREEN | |||||

| 2000 | 8 | *Bush, G. W. (R) | 685,341 | 781,652 | 45,645 |

The most recent in Arizona's series of political scandals was the investigation and 1996 indictment of Governor Fife Symington on 23 counts of fraud and extortion in connection with his business ventures before he became governor in 1991, and his filing of personal bankruptcy. The case went to trial in May 1997. Convicted of fraud, Symington was replaced by Secretary of State Jane Hull, also a Republican. In 1998 gubernatorial elections, Hull was elected in her own right. Janet Napolitano was elected governor in 2002. In 2003, the Arizona Supreme Court decided to individually review the death sentences of 27 inmates by judges rather than juries, which was a practice deemed unconstitutional by the US Supreme Cout.